TLDR¶

• Core Points: Researchers at TU Wien etched the smallest QR code to date on ceramic film, spanning 1.98 square micrometers with 49-nanometer pixels.

• Main Content: The feat demonstrates nanoscale data encoding on ceramic materials, aiming to enable ultra-compact data storage and robust, high-density surfaces for specialized applications.

• Key Insights: Nanoscale QR codes on ceramics could enable unique tagging and data retrieval in harsh environments, but face challenges in readout speed, fabrication consistency, and integration with existing systems.

• Considerations: Practical deployment requires scalable manufacturing, durable read/write processes, and standardized readout interfaces for micro- and nano-scale codes.

• Recommended Actions: Monitor advancements in nanoscale lithography, develop robust readers, and explore use cases in aerospace, medicine, and secure tagging where ceramic stability matters.

Content Overview¶

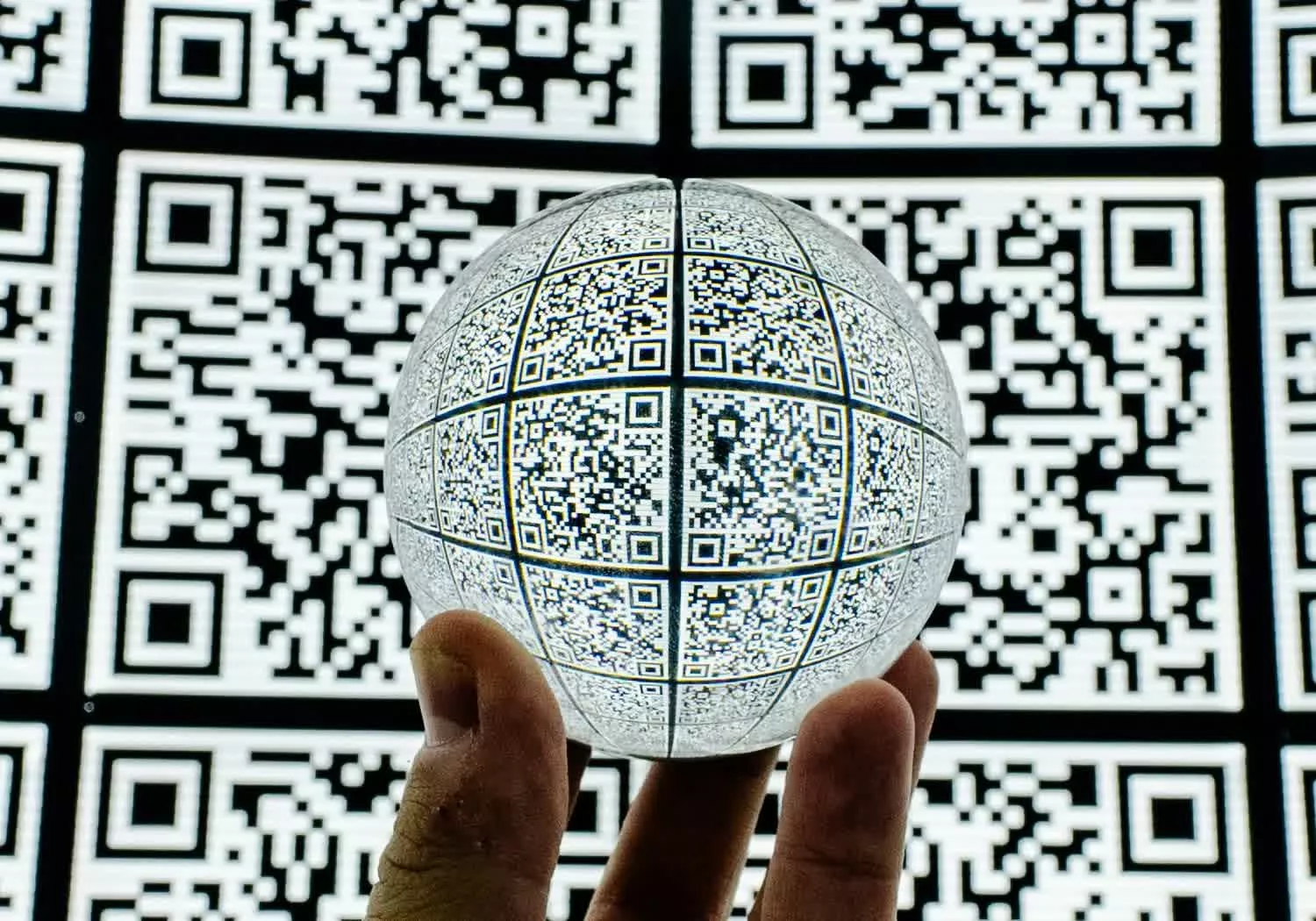

Base on a recent report from TechSpot summarizing research from the Vienna University of Technology (Technische Universität Wien, TU Wien), the team has advanced the concept of data encoding by literally etching a functional QR code onto a ceramic substrate at an unprecedented scale. The etched code covers an area measuring 1.98 square micrometers and features individual data pixels approximately 49 nanometers in size. In practical terms, this means that a QR code, typically seen as a two-dimensional optical code, can be embedded within a ceramic material at the nanoscale, enabling potential high-density data storage and durable labeling in environments where conventional materials may degrade.

The achievement sits at the intersection of materials science, nanofabrication, and information encoding. Ceramics are known for their hardness, chemical resistance, and thermal stability, making them attractive for applications where data integrity must be preserved under extreme conditions. By transferring the concept of a QR code into the sub-mmicron regime, the researchers push the limits of how and where information can be stored and retrieved.

While the news emphasizes the novelty and precision of the nanoscale etching, it also raises questions about practical readout methods and integration with broader data systems. Reading a QR code at the nanoscale involves advanced imaging or detection techniques capable of discerning features at tens of nanometers—a nontrivial requirement given current optical and scanning probe methodologies. The research team’s stated aim extends beyond a single demonstration; they are exploring pathways to scalable fabrication, reliable readout, and potential real-world applications where ceramics’ resilience can be exploited.

This report provides a structured look at the significance, technical considerations, potential applications, and future hurdles associated with etching the world’s smallest QR code onto ceramic film. The discussion situates the development within broader trends in data storage miniaturization, nanofabrication, and the push to create more durable data carriers for challenging environments.

In-Depth Analysis¶

The TU Wien project represents a bold cross-disciplinary effort, combining nanofabrication techniques with information encoding formats. The core achievement is twofold: shrinking the QR code geometry down to an area of 1.98 square micrometers and preserving legibility of the code’s data structure with pixel dimensions of around 49 nanometers. This combination is notably ambitious for several reasons.

First, QR codes rely on a specific pattern of finder patterns, timing patterns, and data modules to enable robust decoding across various orientations and distortions. Transferring this concept to the nanoscale requires meticulous control over lithographic processes to ensure that the resulting pattern remains distinguishable under a readout system. The ceramics used for etching must support high-resolution patterning without compromising the material’s intrinsic advantages, such as hardness, thermal resistance, and chemical stability. It is unclear from the summary whether the researchers employed advanced techniques like electron-beam lithography, focused ion beam milling, or other nanoscale patterning methods, but such methods are typically required to achieve sub-50-nanometer feature sizes.

Second, the practical utility of nanoscale QR codes hinges on the ability to read them reliably. Conventional QR codes are designed for optical scanning with cameras at macro- to microscale resolutions. Reading nanometer-scale features would demand high-resolution imaging modalities or indirect readout schemes, potentially involving scanning probes, electron microscopy, or specialized sensing platforms that can resolve features well below the diffraction limit of visible light. The need for a compatible reader ecosystem is a critical consideration in assessing the viability of the technology beyond a laboratory demonstration.

Third, the choice of a ceramic substrate introduces advantages and challenges. Ceramics can withstand elevated temperatures, harsh chemicals, and mechanical wear better than many polymers or organic media. This resilience makes ceramic-encoded QR data attractive for applications where data carriers are exposed to extreme environments—for example, aerospace hardware, turbine components, or medical devices operating under stringent sterilization and sterilization cycles. On the trade-off side, integrating nano-etched ceramic elements with existing data infrastructure requires compatible readers and data transfer protocols. It also raises questions about storage density, error correction, and data retrieval speed.

From a materials science perspective, the process control necessary to consistently reproduce a 49-nanometer pixel pattern across the 1.98-square-micrometer area is nontrivial. The uniformity of the etched features, the cleanliness of the pattern boundaries, and the absence of unintended material redeposition can all impact readability. Moreover, any surface roughness or sub-surface damage induced during fabrication could affect the optical or electronic signals used for readout.

The broader context of this work includes the ongoing trend toward nanoscale data storage and the exploration of alternative substrates that may outperform conventional media in specific environments. While today’s mainstream data storage emphasizes increasing bit density through magnetic, optical, or resistive memory technologies, the notion of embedding data in durable ceramics at the nanoscale aligns with niche requirements—high-temperature operation, chemical inertness, and long-term stability where typical polymer-based labels would degrade.

The researchers’ stated objective, as summarized in the TechSpot report, is to explore not just the feasibility of nano-etched QR codes on ceramic films but also to address the scalability of the fabrication process and the practicality of data retrieval. The leap from a single proof-of-concept etched code to a scalable manufacturing method involves a series of technical milestones: improving lithography throughput, reducing fabrication costs, ensuring consistent feature sizes across larger areas, and developing robust, curve-tolerant decoding algorithms that can tolerate typical nanoscale imperfections.

In reading such work, it is important to distinguish between a laboratory demonstration and a deployable technology. A crucial question is whether the nanoscale QR code could be read by conventional QR scanners, or if it necessitates specialized instrumentation. The answer to this determines potential application domains. If ultrasensitive imaging or electron-based detection is required, deployment would likely remain limited to specialized facilities. If, conversely, a practical nanoscale decoding system can be integrated into existing scanning platforms or if a new class of readers can be developed to leverage specific ceramic properties, the technology could move closer to real-world use cases.

Ethical and security considerations also emerge when discussing ultra-dense data encoding on solid substrates. As data density on local components increases, the potential for tampering, counterfeiting, or unauthorized data extraction grows. Securing nanoscale data on robust substrates could become important for anti-counterfeiting measures, provenance tracking, or protection of sensitive identifiers on components used in critical infrastructure. On the other hand, the same technology might pose challenges for privacy if nano-labels are placed on consumer items without explicit consent or awareness.

Finally, the interdisciplinary nature of this work is notable. Chemists, physicists, materials scientists, and information theorists must collaborate to optimize both the fabrication process and the data encoding and decoding strategies. Realizing a practical nanoscale QR code on ceramics would require synchronized advances across nanofabrication techniques, surface chemistry, and signal processing algorithms.

Perspectives and Impact¶

The potential implications of etching the smallest QR code on ceramic films reach into several domains:

Hard-wearing labeling: In industrial settings, components are subjected to high temperatures, corrosive chemicals, and abrasive wear. A nanoscale QR code embedded in ceramic components could serve as a durable tag for inventory, maintenance history, or authentication data that remains intact where conventional labels would degrade.

High-density tagging: As devices become smaller and components more integrated, the need for compact, legible identifiers grows. Nanoscale QR codes offer a route to ultra-dense tagging capabilities, enabling more information to be associated with a given object without increasing its physical footprint.

*圖片來源:Unsplash*

Anti-counterfeiting and provenance: In high-value industries—such as aerospace, pharmaceuticals, or electronics—unyielding data identifiers can help verify authenticity and track provenance through the supply chain. Ceramic-embedded codes that survive rigorous processing could add a layer of security to critical parts.

Harsh-environment sensing: If readout challenges can be overcome, nanoscale ceramic QR codes may find use in environments where conventional data carriers fail. For example, components subject to sterilizing procedures, radiation exposure, or extreme temperatures could still maintain readable identifiers.

Educational and research value: Beyond immediate applications, the achievement demonstrates the capabilities of modern nanofabrication and patterning, contributing to the broader knowledge base about how information can be stored and retrieved at the nanoscale. It can inspire further exploration of alternative materials and encoding schemes.

However, several hurdles must be addressed before widespread adoption:

Readout infrastructure: A robust, scalable, and cost-effective reader ecosystem is essential. This could involve developing compact optical or electronic readers capable of resolving nanometer-scale features, or adopting novel readout modalities tailored to ceramic substrates.

Manufacturing scalability: Translating a nanoscale demonstration into production requires reliable, high-throughput fabrication methods. This includes improving lithography speeds, reducing costs, and achieving reproducible feature sizes across larger substrate areas.

Data integrity and error handling: At such small scales, even minor process variations can introduce errors. Advanced error-correcting codes and robust decoding algorithms will be necessary to ensure reliable data retrieval.

Standardization and interoperability: For practical utility, standardized formats, encoding schemes, and readout interfaces are beneficial. Community-wide agreement on how nanoscale QR codes are implemented and read will accelerate adoption.

Environmental and safety considerations: While ceramics are generally inert, nanofabrication processes can involve hazardous materials or procedures. Safe handling, waste management, and compliance with regulatory guidelines will be critical as technologies scale.

Overall, the work embodies a frontier in nanoscale information encoding on durable substrates. While immediate commercial impact may be limited by readout and manufacturing challenges, the concept expands the design space for data carriers that must endure demanding environments and compact form factors.

Key Takeaways¶

Main Points:

– TU Wien researchers etched the smallest QR code on ceramic film to date, measuring 1.98 square micrometers with 49-nanometer pixels.

– Ceramics’ durability offers potential advantages for data tagging in harsh environments, though readout at nanoscale remains a core challenge.

– The project emphasizes both proof-of-concept and the need for scalable fabrication and compatible readout technologies.

Areas of Concern:

– Readout mechanisms capable of resolving 49 nm features in a practical setting.

– Ensuring reproducibility and manufacturing scalability for real-world deployment.

– Integration with existing data systems and development of standardized decoding protocols.

Summary and Recommendations¶

The achievement of etching the world’s smallest QR code onto a ceramic surface marks a notable milestone in nanoscale data encoding. By compressing a QR data structure into an area of 1.98 square micrometers and using 49-nanometer pixels, the TU Wien team demonstrates the feasibility of embedding high-density information within durable substrates. This capability holds promise for specialized applications in which data integrity must endure extreme conditions, such as aerospace components, industrial equipment, and medical devices that undergo rigorous sterilization or environmental exposure.

Despite the promise, translating this laboratory success into practical, scalable technology requires solving several intertwined challenges. Chief among these are developing reliable readout systems that can detect and interpret nanoscale patterns, achieving high-throughput fabrication methods, and ensuring robust error correction and standardization for data retrieval. The progress in this area will likely depend on collaborative advances across nanofabrication, materials science, optical and electronic sensing, and data encoding theory.

If these hurdles can be overcome, nanoscale ceramic QR codes could complement existing labeling and identification strategies, offering ultra-dense, durable data carriers that withstand environments where conventional media fail. Potential next steps include exploring reader architectures tailored to ceramic nanostructures, investigating alternative materials with similar stability properties, and conducting application-specific studies to identify the most compelling use cases—ranging from critical hardware tagging to secure anti-counterfeiting measures.

Overall, the research contributes to a broader narrative in data storage: pushing the boundaries of how and where information can be stored, while balancing practicality with the enduring benefits of material resilience. The next phases will determine whether nanoscale ceramic QR codes become a specialized tool for niche applications or a new standard that informs the design of future data carriers.

References¶

- Original: https://www.techspot.com/news/111378-etching-world-smallest-qr-code-ceramic-pushes-data.html

- Additional context on nanoscale data encoding and ceramic materials (academic and industry sources to be appended as relevant):

- Article on nanoscale lithography techniques and patterning challenges

- Review on durable substrates for data tagging in harsh environments

- Reports on readout technologies capable of sub-50-nm feature resolution

Forbidden:

– No thinking process or “Thinking…” markers

– Article starts with “## TLDR” and is otherwise original and professional.

*圖片來源:Unsplash*