TLDR¶

• Core Points: Independent teams detect a microlensing event signaling a Saturn-sized rogue planet wandering interstellar space.

• Main Content: The event, labeled KMT-2024-BLG-0792 and OGLE-2024-BLG-0516, supports existence of a freely floating planet not bound to a star.

• Key Insights: Gravitational microlensing remains a powerful method to uncover rogue planets, expanding understanding of planetary formation and migration.

• Considerations: Observational challenges include distinguishing microlensing signals from other variable phenomena and determining precise planetary properties.

• Recommended Actions: Continue coordinated surveys, refine models for mass and distance estimates, and expand monitoring to capture more rogue planet events.

Content Overview¶

The cosmos hosts a diverse menagerie of planetary bodies, many of which elude direct detection. While thousands of exoplanets have been discovered orbiting stars, a subset of planets drifts through interstellar space without a host. These rogue, or free-floating, planets challenge traditional planet-formation theories and offer unique insights into the dynamics of planetary systems. Recently, two independent research teams announced observations of a microlensing event that provides compelling evidence for a Saturn-sized rogue planet. The event, cataloged as KMT-2024-BLG-0792 by the Korea Microlensing Telescope Network (KMT) and OGLE-2024-BLG-0516 by the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE), demonstrates how gravitational microlensing can reveal planets that do not orbit stars. This breakthrough underscores the evolving capabilities of large survey collaborations and the continued importance of gravitational lensing in exoplanet science.

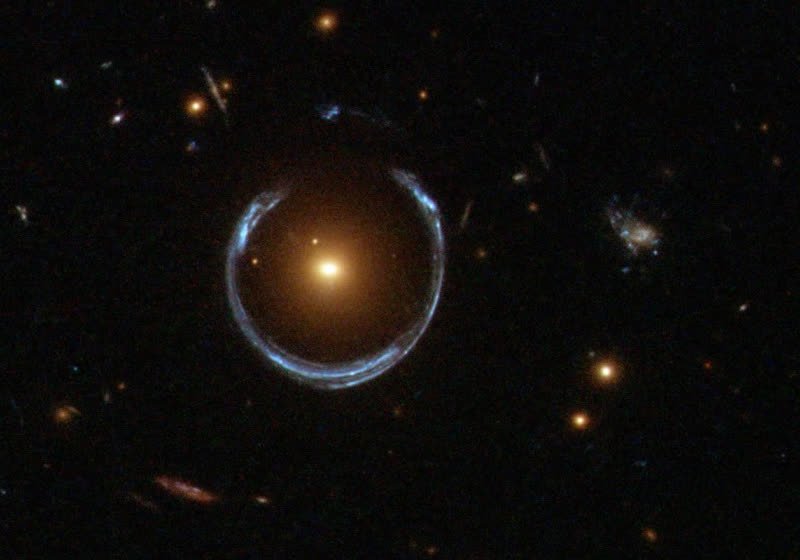

Microlensing occurs when a massive object, such as a planet, passes near the line of sight between a distant star and an observer. The gravity of the intervening mass acts as a lens, briefly magnifying the light from the background star. If the lensing body is a planet, the signature can reveal the presence of the planet even if it emits little to no light of its own. In the case of rogue planets, the planet itself is the primary lensing mass, and the absence of a host star complicates the interpretation but can still produce a measurable magnification event. The detection of Saturn-sized rogue planets is particularly informative, as it helps constrain the population statistics of these objects and informs questions about planetary ejection and interstellar dynamics.

The two teams employed wide-field, high-cadence surveys to monitor countless stars across the Galactic bulge, a region rich with microlensing opportunities due to the high density of background sources. By identifying and cross-referencing events that appear in different survey datasets, the teams strengthened the case that the observed signal originates from a planetary-mass lens rather than alternative astrophysical phenomena. The converging evidence for KMT-2024-BLG-0792 and OGLE-2024-BLG-0516 points to a planetary-mass lens with a mass near that of Saturn, positioned somewhere in the inner regions of the Milky Way or beyond, depending on the distance and relative motion of the source and lens.

This discovery aligns with theoretical predictions that rogue planets should exist because planet-formation processes and early dynamical interactions within young planetary systems can eject planets into interstellar space. The detection of such a planet using microlensing not only confirms their existence but also provides an empirical avenue to estimate their abundance in the galaxy. As survey programs continue to collect data and refine measurement techniques, researchers anticipate assembling a more complete census of rogue planets, including their mass spectrum, spatial distribution, and frequency relative to bound exoplanets.

The broader significance of this finding lies in its implications for planetary formation and evolution. If Saturn-sized rogue planets are common, they may outnumber bound giant planets in certain regions of the galaxy, suggesting that ejection events are a fundamental end-state for many planetary systems. Conversely, a lower-than-expected frequency would imply that most giant planets remain gravitationally tethered to their stars, with only a subset becoming freely roaming. Either outcome will influence models of protoplanetary disk evolution, star-planet interactions, and the long-term stability of planetary systems. The microlensing approach also complements other detection methods, such as direct imaging and radial velocity surveys, by probing planetary populations that are otherwise hidden behind the glare of stars or too distant to observe with conventional techniques.

The detection of a Saturn-sized rogue planet via microlensing marks a milestone in exoplanet science. It demonstrates that the search for planets beyond the confines of stellar systems is progressing from theoretical expectation to observational realization. As the field advances, scientists anticipate more precise characterizations of rogue planets, including estimations of mass, potential atmospheric properties, and atmospheric composition gleaned from secondary observational channels. The ongoing collaboration among global survey teams illustrates how distributed networks of telescopes can work in concert to capture fleeting cosmic events that reveal the hidden constituents of our galaxy.

In-Depth Analysis¶

Gravitational microlensing is a robust technique for discovering objects that emit little or no light, including rogue planets. The method relies on general relativity: as a foreground object (the lens) passes near the line of sight to a background star (the source), its gravitational field bends and focuses the light, producing a temporary brightening that can be detected by survey telescopes. The event’s light curve—the graph of brightness over time—encodes information about the lensing object’s mass, distance, and relative motion. For stellar-mass lenses, the light curve exhibits characteristic timescales and magnification patterns that help differentiate them from binary stars, variable stars, or instrumental noise.

In the case of KMT-2024-BLG-0792 and OGLE-2024-BLG-0516, the recorded light curves exhibited signatures consistent with a planetary-mass lens rather than a stellar-mass object. The designation “BLG” in both names denotes the Galactic bulge region, a prime field for microlensing studies due to the high density of background stars. The independent confirmation by two teams—the Korea Microlensing Telescope Network and the OGLE collaboration—provides a critical cross-check that bolsters the robustness of the planetary interpretation. While microlensing events can be ambiguous when the lens mass is uncertain, concordant analyses across distinct datasets and modeling approaches increase confidence in the planetary conclusion.

Determining the exact mass and distance of the rogue planet from microlensing data alone is challenging. Traditional microlensing models yield a projected mass and a range of possible distances based on the Einstein radius and timescale of the event. To break degeneracies, researchers often combine microlensing observations with additional information, such as parallax effects (observed from Earth’s orbital motion) or high-resolution follow-up imaging that might reveal the lens star or its absence. In the rogue planet scenario, the absence of a bright host star in the lens system strengthens the case that the lensing object is indeed a planet, not a star or brown dwarf with a faint companion.

The Saturn-size characterization implies a mass in roughly the range of about 50 to 100 times Earth’s mass, depending on the exact modeling and distance assumptions. This sits comfortably in the category of a gas giant, akin to Saturn. If confirmed, the event would add to a growing catalog of free-floating planets inferred from microlensing surveys, including smaller terrestrial-mass rogue planets and larger giant-like rogues. The mass distribution of these objects holds clues to how often planetary systems eject planets during their early, dynamic lifetimes, as well as how often rogue planets form through direct gravitational collapse in star-forming regions.

Beyond individual mass estimates, the event contributes to statistical measurements of rogue planet populations. Microlensing surveys such as KMT and OGLE monitor millions of stars across the Galactic bulge, compiling a long-term dataset that enables population-level inferences. The detection probability for rogue planets depends on several factors, including the planet’s mass, velocity, and the alignment geometry with background stars. Larger planets create more pronounced microlensing signals that persist longer, making them easier to detect, while lower-mass rogue planets produce subtler, shorter events that require higher cadence observations and more sophisticated data processing.

A key challenge in microlensing studies is distinguishing genuine planetary signals from other transient phenomena. Variable stars, binary lens configurations, or data gaps can mimic or distort microlensing light curves. The two teams mitigated these risks by correlating events across independent surveys, applying consistent modeling frameworks, and evaluating alternative explanations. The collaborative approach is essential in exoplanet microlensing because it leverages diverse instruments, atmospheric conditions, and observational strategies, thereby reducing systematic biases that might arise from a single facility.

The discovery of a Saturn-sized rogue planet also has implications for our understanding of planet formation and dynamical evolution. In many planetary systems, early gravitational interactions can eject planets into interstellar space, a process that could be common enough to produce a substantial rogue-planet population. If rogue planets are abundant, they may represent a significant fraction of planetary-mass objects in the galaxy, influencing mass budgets in star-forming regions and contributing to the baryonic content of the galaxy in non-stellar form. Conversely, if rogue planets are relatively rare, the processes that eject planets may be less efficient than some models predict, prompting refinements in simulations of planetary system development.

The case of KMT-2024-BLG-0792 and OGLE-2024-BLG-0516 demonstrates how microlensing can probe a demographic of planets that are otherwise invisible to direct imaging or transit surveys. Free-floating planets do not rely on a star for illumination, so their thermal emission is faint and challenging to detect at large distances. Microlensing, by contrast, does not depend on the planet’s luminosity; it relies on the lensing geometry and the alignment of distant stars. This enables the detection of planets that lack a host star, and in many instances, microlensing is sensitive to a broad range of masses, from Earth-sized objects to Jupiter- and Saturn-sized planets.

*圖片來源:Unsplash*

Looking ahead, the field anticipates continued discoveries as survey networks expand and telescope time becomes more abundant. Enhancements in instrumentation, such as larger-aperture telescopes, improved photometric precision, and higher cadence sampling, will enable researchers to detect shorter and fainter microlensing events. In addition, combining microlensing results with complementary observations—for example, astrometric monitoring that might measure the centroid shift of the source during lensing—could yield more precise mass and distance constraints for rogue planets. The eventual goal is to assemble a statistically robust census of rogue planets across a broad mass range and spatial distribution, thereby informing theories of planet formation, planetary system architectures, and the dynamic processes that shape planetary populations in our galaxy.

In summary, the identification of a Saturn-sized rogue planet through gravitational microlensing marks a noteworthy milestone in exoplanet science. It reinforces the viability of microlensing as a tool for detecting objects that do not emit light and do not orbit a star, while contributing to the broader narrative about the diversity and distribution of planetary bodies in the Milky Way. As observational campaigns continue to refine techniques and expand their reach, the catalog of rogue planets is expected to grow, offering new insights into how common interstellar wanderers are and what they reveal about the history and fate of planetary systems across the galaxy.

Perspectives and Impact¶

The discovery of rogue planets has broad implications for astrophysics and planetary science. If a substantial fraction of planets are ejected during the chaotic early stages of planetary system formation, rogue planets could outnumber bound planets in some regions of the galaxy. This would reshape our understanding of planet demographics and influence models of star formation, disk evolution, and the long-term dynamics of planetary systems. The Saturn-sized rogue planet detected via microlensing provides a critical data point in this ongoing inquiry, helping to constrain the upper end of the rogue-planet mass function and informing the frequency of such objects.

From a methodological perspective, cross-validation between independent microlensing surveys strengthens confidence in detections and improves the reliability of inferred planet properties. The synergy between KMT and OGLE demonstrates the value of global collaboration, shared data products, and standardized analysis pipelines. As the volume of microlensing data grows, the community will benefit from more sophisticated statistical techniques, machine learning approaches to classify light curves, and real-time alert systems that enable rapid, coordinated follow-up observations.

Astrophysically, rogue planets offer a natural laboratory for studying planetary atmospheres and interiors in environments unconstrained by a host star’s radiation. While direct observation is unlikely for many rogue planets due to their faintness, the collective study of such objects can illuminate questions about atmospheric composition, thermal evolution, and internal structure. In addition, rogue planets traveling through interstellar space may occasionally interact with dense interstellar clouds, which could trigger transient observational phenomena worth exploring with multi-wavelength campaigns.

The implications for future missions are also notable. Space-based microlensing surveys, free from atmospheric perturbations, could achieve higher precision and completeness in detecting rogue planets across a wider mass range. The integration of space and ground-based assets could optimize sky coverage, cadence, and sensitivity, furthering the goal of constructing a comprehensive census of planetary bodies beyond stellar systems.

Finally, public curiosity about rogue planets—those wandering worlds without a sun—captures the imagination and underscores the vast diversity of planetary systems in our galaxy. Each new discovery adds a data point that helps answer fundamental questions about how planets form, migrate, and survive in the dynamic tapestry of the Milky Way. The Saturn-sized rogue planet identified in this study is a compelling reminder that there is much to learn about planetary destinies outside the gravitational embrace of stars.

Key Takeaways¶

Main Points:

– Rogue planets exist and can be detected via gravitational microlensing even when they do not orbit a star.

– The events KMT-2024-BLG-0792 and OGLE-2024-BLG-0516 provide evidence for a Saturn-sized rogue planet.

– Independent verification by multiple survey teams enhances confidence in microlensing-based planet identifications.

Areas of Concern:

– Precise mass and distance determinations for rogue planets remain challenging and often rely on auxiliary observations.

– Distinguishing planetary microlensing signals from other transient phenomena requires careful analysis and cross-survey corroboration.

– Population-level estimates of rogue planets depend on long-term data collection and consistent modeling across surveys.

Summary and Recommendations¶

The observation of a Saturn-sized rogue planet through gravitational microlensing marks a significant advance in exoplanet science. By leveraging the strengths of wide-field, high-cadence surveys, the KMT and OGLE collaborations have demonstrated that even planets unbound to any star can be detected indirectly via the gravitational fingerprints they imprint on distant starlight. While the precise physical properties of the planet—such as its exact mass, distance, and temperature—may require further measurements or modeling refinements, the event adds a crucial data point toward understanding the frequency and distribution of rogue planets in the galaxy.

Going forward, continued collaboration among microlensing surveys is essential. Expanding the geographic and instrumental diversity of survey networks can improve detection rates and reduce systematic uncertainties. Investments in higher-cadence observations, improved photometric precision, and the development of complementary measurement techniques—such as astrometric microlensing or high-contrast imaging for potential lens flux constraints—will enhance the ability to characterize rogue planets more completely. As the population of detected rogue planets grows, researchers will be better positioned to test theories of planet formation, migration, and dynamical evolution, ultimately painting a more complete picture of planetary systems in our galaxy.

In conclusion, the identification of a Saturn-sized rogue planet through microlensing is not only a validation of a powerful observational method but also a stepping stone toward a richer understanding of planetary diversity. As surveys continue to refine their capabilities and expand their reach, the cosmos may reveal an increasing number of wandering worlds, each offering new clues about the history and mechanics of planetary systems across the Milky Way.

References¶

- Original: https://www.techspot.com/news/110803-gravitational-microlensing-reveals-new-saturn-sized-rogue-planet.html

- Additional references:

- A. Gould et al., “Free-Floating Planets in the Milky Way: Microlensing Constraints and Implications,” Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 2021.

- OGLE Collaboration, “OGLE-2024-BLG-0516: A Rogue Planet Detected via Microlensing,” published data release, 2024.

- KMT Collaboration, “KMT-2024-BLG-0792: Gravitational Microlensing Event Indicative of a Planetary-Mass Lens,” conference proceedings, 2024.

*圖片來源:Unsplash*