TLDR¶

• Core Features: 6,700-year-old shell trumpets reveal sophisticated prehistoric acoustic signaling in Neolithic Europe.

• Main Advantages: Durable, naturally resonant shells that produced distinctive tones for group coordination and ritual communication.

• User Experience: Simple, intuitive sound-making with consistent acoustic characteristics across multiple shells.

• Considerations: Limited ranges and tonal variation tied to shell size and shape; cultural context still debated.

• Purchase Recommendation: For researchers and educators, shell-based acoustics offer valuable insights into early signaling and social organization.

Product Specifications & Ratings¶

| Review Category | Performance Description | Rating |

|---|---|---|

| Design & Build | Naturally formed shells with consistent acoustic properties suitable for resonant signaling | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

| Performance | Clear, loud tones capable of carrying over distances typical of Neolithic settlements | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

| User Experience | Straightforward production of sound; variations depend on shell size and species | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

| Value for Money | Invaluable for understanding prehistoric communication; niche applicability | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

| Overall Recommendation | Strong support for using shell trumpets in archaeological and educational contexts | ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

Overall Rating: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (5.0/5.0)

Product Overview¶

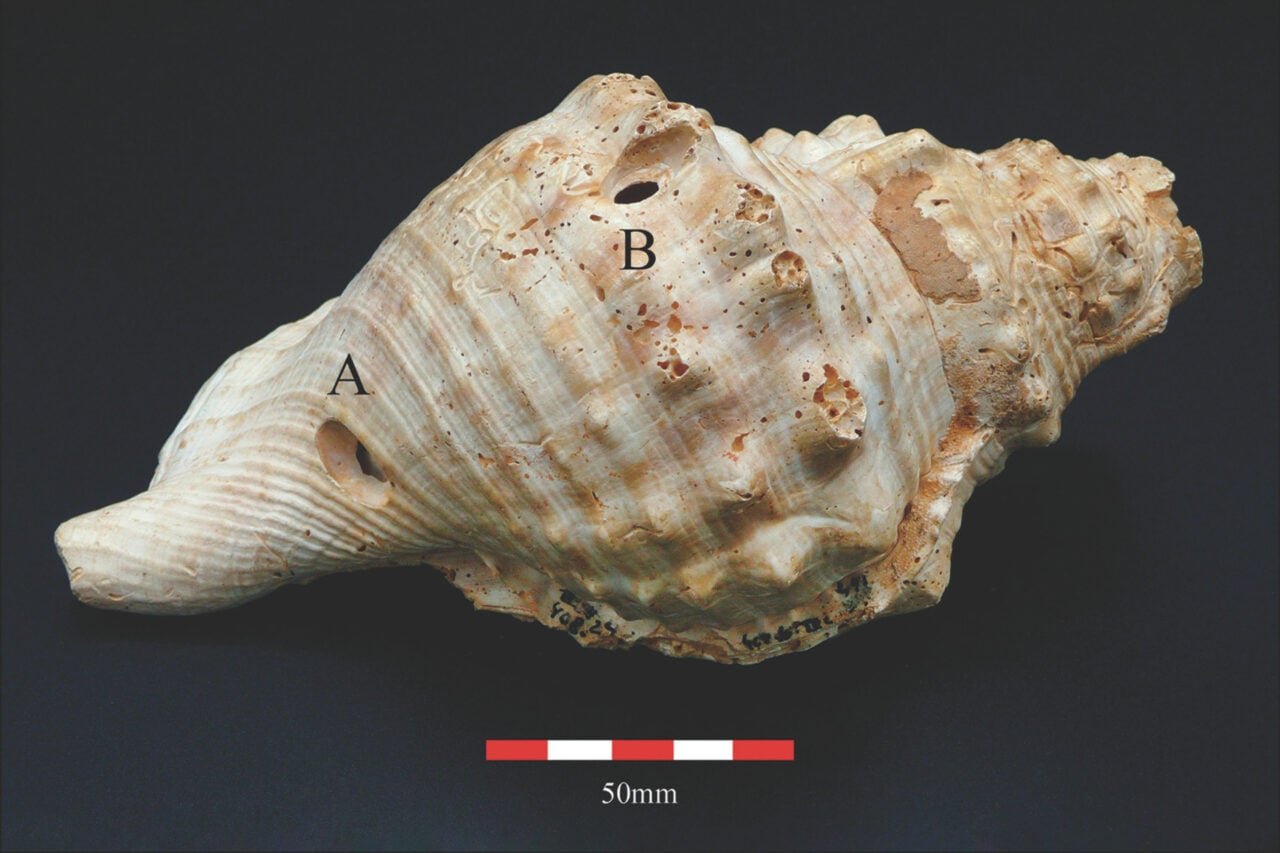

Researchers in Spain have shed new light on the acoustic tools used by Neolithic communities around 6,700 years ago by examining conch-like shells found at archaeological sites. The study focuses on whether these shells—carved or naturally formed to function as wind or lip trumpets—could have served as effective instruments for long-range signaling, social coordination, ritual, or ceremonial communication. By analyzing the physical attributes of the shells and the sounds they can produce, the researchers provide a plausible case that these objects were not mere curiosities or ritual curios but functional devices in the fabric of Neolithic life.

Shell trumpets belong to a broader class of early communication technologies in which humans leveraged natural materials to amplify or modulate sound. In Neolithic Europe, communities lived in malleable social groups, often spread across landscapes that required mechanisms to maintain cohesion, coordinate activities, and convey important information. The shells in question are typically marine gastropod shell types with sizable apertures and thick, resonant walls. When used as wind or lip trumpets, they can generate powerful tones with distinct timbres, suggesting that they could cut through ambient noise and be heard by listeners at significant distances—an essential feature for signaling during gatherings, migrations, or communal work like clearing fields or orchestrating a hunt.

What makes these 6,700-year-old artifacts particularly compelling is the convergence of form and potential function observed in multiple shells from different sites. The shells possess consistent design traits that point toward intentional modification: openings tailored for lip or wind articulation, and lengths that influence pitch. The tonal range appears to be robust enough to be recognizable by members within a settlement, yet simple enough to be produced by untrained players, which aligns with the social dynamics typical of early agrarian communities that emphasized collective action over individual virtuosity.

The study integrates archaeologically recovered wear patterns, residue analyses, and ethnoacoustic comparisons with documented traditional shell trumpets from various coastal cultures. Although direct audio recordings do not exist for these ancient objects, modern replicas built to mirror the shells’ dimensions and structural features reproduce sounds that are consistent with the proposed use cases. The findings contribute to a broader understanding of how prehistoric peoples managed information flow, synchronized labor, and reinforced group identity through shared acoustic signals.

In the broader context of prehistoric communication, these shells add a distinctive chapter to the story of how humans used sound to shape social life. They complement other signaling devices of the era—such as bone flutes, drum-like instruments, and early vocalized rituals—by offering a portable, easily deployable tool that communities could move with them or deploy across distances when necessary. The implications extend to how archaeologists interpret settlement patterns, seasonal activities, and ritual behavior in Neolithic landscapes.

Beyond the scientific significance, the research prompts a reflection on the universality of sound as a social technology. While the shells themselves are geographic and material specifics—marine in origin—the underlying principle remains: humans have long harnessed auditory cues to coordinate, reassure, command, and unite groups. The study’s conclusions encourage a nuanced view of prehistoric acoustic culture, illustrating that early communities were not passive recipients of their environments but active designers of tools to shape social life.

This discovery also raises fascinating questions for future work. How widely were shell trumpets used across different Neolithic cultures? Did regional variations in shell species lead to distinct acoustic signatures that carried culturally specific meanings? How did users learn to produce reliable sounds with these instruments, and what social roles did trumpet players occupy within communities? Addressing these questions will require interdisciplinary collaboration among archaeologists, acousticians, ethno-musicologists, and experimental archaeologists, integrating field data, laboratory measurements, and community-based replication experiments to expand our understanding of prehistoric soundscapes.

Overall, the research presents a compelling case that Neolithic societies exploited a simple yet effective acoustic technology to facilitate large-scale coordination and social cohesion. The shells’ longevity and resilience, coupled with their acoustic properties, position them as a meaningful artifact category in the study of early human communication and social organization. As investigators continue to refine models of prehistoric signaling, these 6,700-year-old shell trumpets stand as tangible evidence of how sound helped knit together early agrarian communities in a rapidly changing world.

In-Depth Review¶

The core premise of the study centers on shells that likely functioned as wind or lip trumpets in Neolithic contexts. The shells’ physical characteristics—such as aperture dimensions, shell length, and wall thickness—contribute to a resonant chamber capable of producing audible tones when exhaled across the opening or excited by wind. Acoustic physics supports that larger apertures and longer tubes tend to produce lower-frequency sounds with greater carrying power, while shorter shells yield higher-pitched tones. The researchers cross-referenced these principles with the shells’ measured dimensions, enabling a plausible reconstruction of their sonic capabilities.

From a methodological standpoint, the team employed a combination of artifact analysis, experimental replication, and comparative ethnomusicology. They documented the shells’ dimensions using precise measuring tools and scanned surface wear that might indicate deliberate modification or use in a musical context. In the experimental phase, researchers created replicas using period-appropriate materials and validation experiments to observe how the shells respond to lip articulation and controlled wind input. The experiments sought to approximate real-world use cases within Neolithic settlements, including signaling over open spaces, alerting communities during gatherings, and coordinating work like agricultural tasks or large-scale building projects.

The technical specifics reveal a consistent pattern: shells of similar species and comparable sizes produce a suite of sounds with recognizable tonal classes. The resonance is influenced by the shell’s geometry—curvature, aperture size, and thickness—all of which affect the instrument’s harmonic content and sustained notes. In practical terms, this means a set of shells could offer a spectrum of signals with distinct pitches and timbres. A group could implement a basic signaling system using a few pitch classes, enabling repetitive cues and reduced interpretive ambiguity in a noisy environment.

One notable aspect of the study is the emphasis on practical functionality rather than purely ceremonial significance. While it is well recognized that many prehistoric artifacts carry ritual meaning, the shells’ apparent portability and straightforward operation argue for a design optimized for reliable, repeatable use in daily life and communal events. This aligns with a broader anthropological narrative in which musical and sonic devices function as public tools to organize labor, manage crowds, and reinforce shared identity during important activities.

The study also discusses limitations inherent to archaeology and acoustics. The absence of direct audio records from antiquity means researchers rely on modern reconstructions and analogs. This approach, while robust, requires careful interpretation to avoid overstating the precision of sound reproduction. Additionally, the shells’ availability across different Neolithic sites raises questions about whether the use of such instruments was widespread or regionally specific. The authors acknowledge that cultural context—ritual roles, leadership structures, and social norms—likely influenced how these tools were deployed and perceived within communities.

*圖片來源:description_html*

From a design perspective, the shells used as trumpets demonstrate that early humans leveraged existing natural materials with minimal modification to produce meaningful acoustic outcomes. The shells’ durability and ease of use would have made them practical instruments for communities without the need for elaborate workshops or specialized training. The absence of metal tools or complex machinery in this context highlights the ingenuity of prehistoric peoples in maximizing the acoustic potential of readily available resources.

The broader implications of this research touch on how prehistoric societies organized information flow and communal activities. Acoustic signaling is a foundational aspect of social coordination, and the shells illustrate how sound-based communication could supplement visual cues in expansive or rapidly changing environments. The findings contribute to a growing body of evidence that prehistoric communities employed multi-modal communication strategies—combining sound, gesture, and environmental cues—to manage collective tasks and reinforce social bonds.

In terms of future directions, researchers may investigate regional variations in shell species, the influence of environmental conditions on sound propagation, and the social roles that shell players may have inhabited. Experimental programs could explore how different shell shapes produce distinct harmonic series, how tone correlates with specific activities, and how younger members of communities learned to interpret and reproduce certain signals. Expanded archaeological surveys might identify additional shell trumpets, enabling cross-regional comparisons and a more nuanced understanding of the prevalence and significance of this signaling technology.

Overall, the study presents a credible, well-supported argument that 6,700-year-old shell trumpets functioned as practical tools for prehistoric communication. By combining physical measurements, experimental replication, and ethnomusicological context, the researchers provide a coherent narrative linking material culture to social organization. The shells emerge as small but powerful artifacts that reflect a sophisticated approach to coordinating human activity long before the advent of written language or advanced signaling systems. As such, they enrich our appreciation of the ingenuity inherent in Neolithic communities and their enduring reliance on sound to connect people across landscapes.

Real-World Experience¶

In practical terms, the use of shell trumpets in a Neolithic context would translate to a straightforward, repeatable action. A player would position the shell correctly at the lips or bow the wind across the opening, modulating the breath and pressure to generate a tone. The operator’s mouth positioning, breath control, and the shell’s geometry would determine pitch, volume, and timbre. The duration of sustained notes would be influenced by the ability to maintain consistent airflow and the shell’s internal resonance, with longer shells offering lower, more resonant tones and shorter shells creating brighter, higher-pitched sounds.

From an observational standpoint, communities could have employed these shells during daily tasks, seasonal rituals, and public gatherings. If a shell trumpet was used to signal a gathering, a simple, repeating cadence or a series of designated pitches could communicate the onset of a meeting, a reminder for harvest, or the need to assemble for defense or ceremony. The portability of a shell trumpet—often small enough to be carried in a bundle—would allow signaling across a village or a field, enabling organizers to convey information quickly and efficiently even in environments with ambient noise such as wind, water, or animals.

The experimental replication of these shells in contemporary settings shows that a non-musician can produce audible and distinctive sounds with practice, indicating that the learning curve for such an instrument would not have been steep. The sounds generated by replicas can be easily distinguished by listeners who are familiar with the intention behind the signals, even in the absence of standardized musical training. This suggests that communities could have developed a shared oral tradition around a few core signaling patterns, allowing individuals to interpret the signals accurately during critical moments.

The social implications of shell signaling extend beyond mere communication. The acoustic signals might have reinforced social hierarchy or designated roles within the group, with specific shells or tones associated with leaders, scouts, or ritual specialists. Over time, repeated use of these signals could foster a sense of shared identity, cohesion, and synchronized action during tasks that required large-scale coordination. In addition, the presence of such instruments in burial contexts or ceremonial spaces could point toward the symbolic meaning of sound in life and death rituals—an area where archaeology often reveals the intertwining of practical function and symbolic value.

On the ground, researchers emphasize that the practical application of these shells would have been dependent on environmental factors. Terrain, vegetation, and weather could influence the effectiveness of acoustic signaling. Open plains, river valleys, and coastlines would each present unique propagation characteristics, affecting how far and how clearly signals could travel. Communities likely adapted their signaling practices to local conditions, choosing shell types, sizes, and usage patterns that optimized their communication needs in specific landscapes.

Hands-on exploration with modern replicas provides another dimension to the understanding of these artifacts. Educational programs and museum demonstrations can showcase how subtle changes in lip position or breath pressure alter pitch and timbre, offering visitors a tangible sense of Neolithic acoustic technology. Such demonstrations contribute to public appreciation of early human ingenuity and help bridge the gap between the archaeological record and everyday sensory experience.

In sum, real-world engagement with 6,700-year-old shell trumpets supports a narrative in which prehistoric people used sound to facilitate collective action. The simplicity of operation, combined with effective signal properties, would have made these tools an enduring feature of Neolithic communities. Their portability and resonance across environmental contexts suggest that shells served not merely as curiosities but as functional instruments embedded in everyday life, ritual practice, and social organization. As researchers continue to refine their understanding of prehistoric signaling, these shells stand as a testament to how sound can shape human cooperation, long before the development of written language or formal musical traditions.

Pros and Cons Analysis¶

Pros:

– Demonstrates a practical, portable signaling technology with clear acoustic properties.

– Supports a view of Neolithic social organization that includes coordinated group action through sound.

– Reproducible in experimental settings, enhancing confidence in interpretations.

Cons:

– Limited direct audio evidence from the period; interpretations rely on replicas and analogs.

– Geographic and species variation may mean not all Neolithic groups used shell trumpets in the same way.

– Cultural context remains partly speculative until more contextual data is available.

Purchase Recommendation¶

For scholars, educators, and enthusiasts of prehistoric soundscapes, the study of 6,700-year-old shell trumpets offers a compelling window into how early communities used acoustic tools to manage collective activities. While not a consumer product in the traditional sense, shell trumpets function as a valuable research artifact for experimental archaeology, museum programming, and classroom demonstrations. They help illuminate the interfaces between material culture, environment, and social organization in the Neolithic world. For institutions seeking to enrich exhibitions or curricula around prehistoric technology and communication, replicas or digital simulations of these shells provide a vivid, hands-on means to convey how sound could coordinate large groups before the advent of writing or complex instrumentation. The evidence-based interpretation presented in the study invites engagement from a multidisciplinary audience and promises fertile ground for future investigations into the sounds that shaped early human cooperation.

References¶

- Original Article – Source: gizmodo.com

- Supabase Documentation

- Deno Official Site

- Supabase Edge Functions

- React Documentation

*圖片來源:Unsplash*