TLDR¶

• Core Points: The EPA closed a loophole allowing xAI to operate methane-fueled turbines without proper air quality permits at the Colossus data center in Memphis, following a challenge by the Southern Environmental Law Center.

• Main Content: Regulators determined the turbines were improperly classified as “non-road” engines, prompting permit requirements and enforcement actions.

• Key Insights: Addressing misclassification of large energy generators is critical for accountability and environmental protection in data-center operations.

• Considerations: The ruling underscores ongoing tensions between rapid data-center expansion, energy use, and regional air quality compliance.

• Recommended Actions: Companies should ensure correct engine classifications and obtain appropriate permits; policymakers should clarify definitions to prevent loopholes.

Content Overview¶

The Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) had pressed concerns about xAI’s off-grid methane-fueled turbines serving the Colossus data center in Memphis. According to SELC, xAI operated these turbines without the requisite air quality permits. The core issue centered on how the company labeled the turbines—classifying them as “non-road engines,” a category typically reserved for temporary or movable generators rather than permanent installations. This misclassification, SELC argued, allowed the turbines to evade the standard permitting process that governs large stationary energy sources and their emissions.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) intervention marks a significant enforcement action in the ongoing domain of air quality regulation for data-center infrastructure. Data centers are energy-intensive facilities, and some operators have explored on-site or off-grid generation as a means to ensure reliability and resilience, particularly in the face of outages or grid instability. However, such configurations must comply with applicable air quality and emissions standards. The case involving xAI in Memphis underscores regulatory scrutiny over how energy assets associated with data centers are permitted and monitored.

The Memphis site has drawn attention to the practical and legal challenges at the intersection of technology infrastructure, environmental law, and public health. Large methane-fueled generators emit pollutants that can affect local air quality, and misclassifying these units risks circumventing oversight meant to regulate emissions. The EPA’s actions, guided by the findings of groups such as SELC, aim to ensure that all significant emission sources associated with the data center receive appropriate permits, emission controls, and ongoing compliance reporting.

This developing story sits within a broader national conversation about how rapidly expanding data-center footprints reconcile with environmental safeguards. As technologists and investors push for more robust and reliable digital infrastructure, regulators are increasingly scrutinizing the environmental footprints of energy solutions deployed by these facilities. The Memphis case could influence future enforcement trajectories, prompting operators to reevaluate their on-site power strategies and permit statuses to align with state and federal environmental standards.

In-Depth Analysis¶

The dispute over xAI’s off-grid turbines hinges on the regulatory distinction between “non-road engines” and permanent, stationary power sources. Non-road engines are generally defined as internal combustion engines used in equipment that is not designed for stationary, long-term operation at a fixed site. They are often subject to different emissions standards and permitting requirements compared with stationary generators. SELC contended that xAI’s classification did not accurately reflect the operational reality of large methane-fueled turbines serving a fixed data-center facility. If the units were indeed operating as part of the Colossus data center’s energy infrastructure, they would likely fall under more stringent permitting and emission-control obligations.

The potential consequence of misclassification is significant. Permits for large combustion sources typically require air quality modeling, emission limits, monitoring, reporting, and, in some cases, emission control technologies. Without such permits, operators may avoid compliance costs and oversight, creating a discrepancy between actual emissions and what is documented to regulators. The EPA’s role in addressing these issues is to ensure that the actual environmental impact aligns with regulatory expectations and to close loopholes that could undermine air quality protections.

Data centers, by their design, demand high reliability and often pursue diversified power strategies to mitigate the risk of outages. On-site generation and diversified energy sources can provide resilience, but they also introduce regulatory complexities. When a facility relies on large, methane-fueled turbines, the emissions profile can be substantial, particularly for volatile organic compounds (VOCs), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and methane itself. Methane, while less directly tied to urban smog than NOx or particulates, is a potent greenhouse gas with climate implications, and its capture or combustion efficiency is an important consideration for lifecycle emissions.

The Memphis case involves a balancing act between ensuring continuity of service for Colossus’s operations and upholding environmental standards designed to protect air quality. The EPA’s decision to shut down or restrict the off-grid turbine operation at the site, in response to the misclassification concerns, is consistent with a broader federal emphasis on preventing emission offsets that could erode air quality protections. The agency’s action likely involved a review of the turbine’s capacity, fuel type, and the regulatory framework under which such devices fall. If the turbine capacity exceeds certain thresholds, or if the installation constitutes a stationary source, it would be subject to Title V operating permits and other related regulatory requirements.

The Southern Environmental Law Center has played a pivotal advocacy role by highlighting potential gaps between actual operations and permitted use. Environmental law groups frequently pursue such matters through administrative complaints, settlement agreements, or lawsuits, aiming to secure compliance and, in some cases, force equipment retrofits or shutdowns. SELC’s involvement reflects the watchdog role played by environmental organizations in monitoring large-scale energy use and the potential environmental and public health impacts of emissions from data-center support infrastructure.

For xAI, the regulatory outcome could necessitate a range of corrective actions. These could include reclassifying the turbines to reflect their actual operation, applying for the necessary air permits, deploying emission-control technologies, or modifying the energy strategy to rely more heavily on grid power or approved on-site generation that complies with regulatory standards. The cost implications of such adjustments can be meaningful, particularly for facilities that require steady, high-capacity power. Retrofitting or replacing off-grid generation with compliant equipment may require downtime, capital expenditure, and a restructured maintenance and monitoring program to ensure ongoing compliance.

The Memphis decision also informs state-level environmental policy and enforcement. States regulate air quality and permitting for stationary sources through a combination of state implementation plans (SIPs), air-quality rules, and delegated authorities from the EPA. When the federal government asserts that a company has misclassified equipment or bypassed necessary permits, it can trigger state-level investigations, supplemental permits, or enforcement actions such as consent decrees or penalties. The outcome in Memphis could set a precedent for other data-center operators to review their own energy configurations and ensure alignment with permit requirements, particularly for methane-fueled generation and off-grid setups.

In terms of public health and community impact, enforcement actions targeting emissions from energy generation near urban and suburban areas carry significance. While a data center may operate in a specialized industrial corridor, its energy infrastructure interacts with nearby residential communities. Emissions from large combustion sources can contribute to local air quality degradation, especially during periods of high demand or when multiple facilities operate concurrently. Regulators often weigh the benefits of reliable digital infrastructure against potential environmental and health costs, and actions like these signals demonstrate a commitment to maintaining air quality standards amidst the growth of data-center capacity.

The broader regulatory landscape includes ongoing debates about how to classify energy generation technologies and the responsibilities of data-center operators to monitor and report emissions. The EPA, in conjunction with state environmental agencies, has pursued clarifications on what constitutes a stationary source vs. a mobile or non-road engine, and under what conditions permitting is required. The Memphis case could catalyze industry-wide discussions about standardizing classifications and aligning them with emission-control technologies and reporting requirements.

From a technological perspective, improvements in on-site generation technologies, such as methane-fueled turbines, continue to evolve. Advances may include greater efficiency, reduced emissions through better combustion and after-treatment, and integration with energy storage to smooth out fluctuations in power demand. Operators might explore hybrid approaches that combine grid power with refueling-driven generation, enabling resilient performance while maintaining compliance. Nevertheless, regulatory clarity remains essential to ensure that innovations in energy strategy do not outpace environmental safeguards.

Overall, the Memphis episode highlights how environmental law, energy policy, and technology deployment intersect in modern data-center operations. It demonstrates that even seemingly technical issues—how a machine is classified for regulatory purposes—can have outsized implications for permits, compliance costs, and the broader environmental footprint of digital infrastructure. As data centers continue to grow their energy needs to support cloud services, AI workloads, and other compute-intensive tasks, regulators will increasingly scrutinize the siting, design, and operation of energy assets that power these facilities.

Perspectives and Impact¶

- Regulatory Clarity and Consistency: The case underscores the need for precise, uniform definitions of terms such as “non-road engines” and “stationary generators” across federal and state programs. Ambiguity in classification can create permitting gaps that operators might exploit. Clarified regulations would help prevent similar loopholes and reduce regulatory uncertainty for businesses planning large-scale infrastructure.

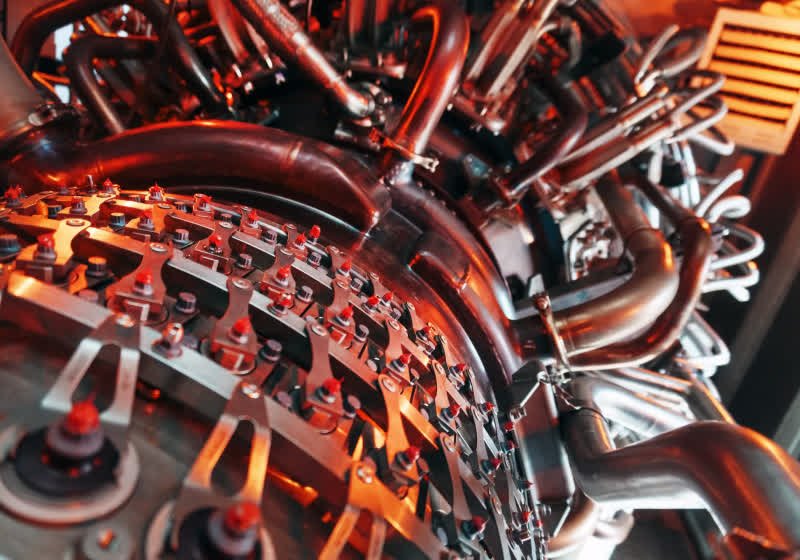

*圖片來源:Unsplash*

Environmental Protection vs. Infrastructure Reliability: Regulators must weigh the environmental implications of on-site energy generation against the operational requirements of high-demand data centers. While on-site generation can bolster reliability and resilience, it also expands emissions sources near populated areas. The Memphis action reflects a preference for ensuring that energy strategies are both robust and compliant.

Economic Considerations for Data Centers: For operators, the cost of obtaining permits, installing emission-control systems, or transitioning to alternative energy sources can be substantial. However, the enforcement action signals a fair playing field where all facilities must meet the same environmental standards. In the long term, predictable regulatory frameworks can benefit the industry by reducing enforcement risk and reinforcing reputational trust with customers concerned about sustainability.

Public Health and Community Impacts: The enforcement action aligns with public health goals by ensuring that emissions from large turbines receive appropriate oversight. Communities near data-center corridors can benefit from improved air-quality protection, particularly if corrective actions lead to better emissions performance or scrubber implementation.

Policy Implications and Precedent: The Memphis case could influence state and federal regulators to tighten enforcement of permit requirements for off-grid or back-up generation tied to critical infrastructure. If successful, similar actions may be taken against other facilities with comparable configurations, prompting a broader review of energy strategies in the technology sector.

Industry Dynamics and Innovation: The ruling may incentivize developers and operators to invest in cleaner generation technologies, energy efficiency measures, or complementary energy storage solutions. By integrating more transparent permitting processes with advanced energy management, data-center operators can align innovation with environmental stewardship.

Legal and Advocacy Dimensions: This case illustrates how environmental organizations, such as SELC, can contribute to regulatory enforcement by highlighting gaps in permit coverage. The interaction among advocacy groups, federal agencies, and industry players shapes the regulatory landscape and can lead to more robust protections over time.

Future Enforcement Trends: As data centers scale globally, regulators may extend emissions oversight to a broader array of ancillary equipment. The Memphis action highlights the likelihood of continued scrutiny over the regulatory status of on-site generation assets and may prompt the development of standardized reporting and verification frameworks.

Climate Considerations: Large methane-fueled turbines contribute to greenhouse gas emissions if methane is not fully combusted or captured. Aligning such assets with best practices for methane management and energy efficiency can support broader climate objectives, particularly as data centers expand their carbon accounting and sustainability reporting.

Stakeholder Communication: For xAI, transparent communication with regulators, communities, and customers will be essential during remediation. Explaining the steps taken to achieve compliance, the expected timelines for permit issuance or equipment upgrades, and the anticipated environmental benefits can help rebuild trust and demonstrate responsible governance.

Key Takeaways¶

Main Points:

– The EPA challenged xAI’s off-grid methane-fueled turbines at the Colossus data center in Memphis, citing improper classification as non-road engines.

– The enforcement action seeks to ensure appropriate air quality permits and emission controls for stationary energy sources associated with data-center operations.

– The case signals a broader push for regulatory clarity surrounding energy infrastructure tied to digital infrastructure and data centers.

Areas of Concern:

– Potential permits gaps for large energy assets at data centers could lead to unmonitored emissions.

– Balancing data-center reliability with environmental protections requires clear regulatory guidance.

– The possibility of future misclassifications across other facilities raises questions about industry-wide practices.

Summary and Recommendations¶

The Memphis episode involving xAI’s off-grid turbines crystallizes a critical interface between high-tech infrastructure and environmental governance. While data centers are essential for sustaining the digital economy, their energy strategies must be anchored in robust regulatory compliance to safeguard air quality and public health. The SELC’s advocacy, followed by EPA action, demonstrates a commitment to closing regulatory gaps that could enable emissions to go unchecked under misapplied classifications. This case emphasizes the need for precise definitions of engine classifications, transparent permit requirements, and rigorous verification of emissions controls for large energy assets tied to critical infrastructure.

For industry stakeholders, several concrete steps are advisable:

– Immediate assessment of all on-site and back-up energy assets to confirm proper regulatory classification and permit status.

– Collaboration with environmental agencies to determine applicable permits, emission limits, and monitoring requirements for stationary energy sources.

– Exploration of compliant energy alternatives, including advanced clean-energy technologies, energy storage, or grid-reliant configurations that minimize emissions.

– Strengthened internal governance and disclosure around energy infrastructure, emissions reporting, and compliance posture to maintain stakeholder trust.

– Monitoring of regulatory developments at the federal and state level to anticipate changes in permit requirements or definitions that could affect other facilities.

Ultimately, aligning data-center operational resilience with environmental stewardship will require ongoing dialogue among operators, regulators, and communities. As digital infrastructure expands, the Memphis case provides a instructive example of how legal clarifications and enforcement actions can shape the prudent deployment of energy resources in support of our increasingly connected society.

References¶

- Original: https://www.techspot.com/news/110971-epa-shuts-down-xai-off-grid-turbine-loophole.html

- Additional references:

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (General Guidance on Permitting Large Combustion Sources)

- Southern Environmental Law Center. (Advocacy briefs and casework related to data-center emission sources)

- State environmental agency filings and press releases related to the Colossus data center case (Memphis, Tennessee)

Forbidden:

– No thinking process or “Thinking…” markers

– Article must start with “## TLDR”

End of rewritten article.

*圖片來源:Unsplash*