TLDR¶

• Core Points: A study replaces metal/plastic gears with controlled liquid flows to transmit motion, using two submerged cylinders in a viscous water-glycerol mixture.

• Main Content: Demonstrates that fluid dynamics can mimic gear-like transmission, offering a new paradigm for motion transfer at small scales.

• Key Insights: Viscous flows can couple rotating bodies, enabling directional torque transfer without solid teeth; surface conditions and fluid viscosity govern performance.

• Considerations: Practical applications require robust control of flow stability, energy efficiency, and material compatibility; scaling and losses remain key questions.

• Recommended Actions: Encourage interdisciplinary exploration of fluidic gears, pursue optimization of fluids and geometries, and assess integration with microfluidic and soft robotics.

Product Review Table (Optional):¶

No hardware product review is applicable to this article.

Content Overview¶

Traditional gears rely on rigid teeth to transfer motion and torque between shafts. For millennia, engineers have relied on precise tooth profiles, lubrication, and rigid materials to ensure reliable power transmission. A provocative study published January 13 in Physical Review Letters challenges this long-standing paradigm by proposing and testing an alternative mechanism: using controlled flows of liquid to transmit motion between rotating bodies. In a fluidic gear concept, solid teeth or interlocking gear stacks are replaced by carefully organized liquid flow patterns that entrain and drive neighboring components. The experiment, conducted by researchers at New York University, investigates whether viscous fluid dynamics can generate coupling strong enough to function as a gear-like transmission.

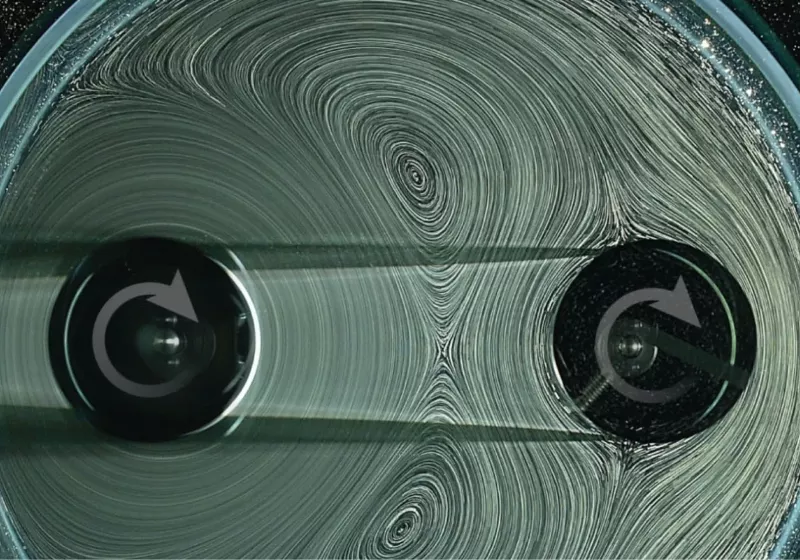

In their experimental setup, NYU physicists submerged two cylinders in a viscous water–glycerol mixture. When one cylinder is spun, it generates a patterned flow field in the surrounding liquid. Under the right conditions, this flow exerts a shear and drag on the second cylinder, causing it to rotate as well. The researchers meticulously varied fluid viscosity, cylinder spacing, and surface properties to observe how effectively rotational motion could be transmitted through the liquid medium. The results indicate that, within a controlled environment, fluid flows can indeed emulate aspects of traditional gearing by directing torque and rotation between components without the need for rigid gear teeth. The findings open the door to a new class of devices that exploit fluid dynamics to achieve precise mechanical coupling, with potential relevance to microfluidics, soft robotics, and energy-efficient motion control.

This line of inquiry sits at the intersection of classical mechanics, hydrodynamics, and materials science. By reframing motion transfer as a problem of fluid-structure interaction rather than gear tooth engagement, researchers aim to harness the predictable, tunable properties of viscous flows. The study further highlights how surface treatment, boundary conditions, and fluid composition can be leveraged to tailor the coupling strength and directionality of motion. While the proof-of-concept experiments focus on a fundamental demonstration, the broader implications extend to how machines at small scales could operate without traditional gears, using carefully engineered liquids as the enabling medium.

In-Depth Analysis¶

The paper’s central claim is that a liquid medium, when properly configured, can serve as an effective conduit for transmitting rotational energy between solids, without the discrete engagement typical of gears. The two-cylinder setup provides a simplified, highly controllable environment to explore this concept. The experiment leverages a viscous water–glycerol mixture to ensure that hydrodynamic forces dominate and that the liquid’s resistance can be tuned. By adjusting the viscosity, the researchers alter the balance between inertial effects and viscous damping, which in turn modulates how efficiently motion is communicated from the driving cylinder to the driven cylinder.

Key observations include the formation of steady, laminar flow patterns around the rotating cylinder, with the nearby stationary cylinder experiencing induced torque due to the viscous drag in the gap region. When spacing is sufficiently small and the fluid is sufficiently viscous, the coupled system can achieve a synchronized rotation that resembles meshing behavior seen in traditional gears, albeit mediated through fluid dynamics rather than mechanical interlocking teeth. The study also emphasizes that the direction of rotation and the magnitude of transmitted torque depend sensitively on boundary conditions, such as surface roughness, slip conditions at the fluid–solid interface, and the precise geometry of the setup.

From a theoretical standpoint, the work rests on classical hydrodynamics, particularly the Stokes flow regime applicable to highly viscous fluids at low Reynolds numbers. In this regime, the flow is linear with respect to driving forces, and superposition principles apply, enabling more straightforward predictions of how changes in viscosity, spacing, or surface characteristics will impact coupling. The researchers’ experimental results align with these theoretical expectations, demonstrating that controlled liquid flows can be tuned to achieve predictable motor-like behavior.

The potential advantages of a liquid-based gear system are multiple. First, it introduces a method to transmit motion without physically contacting gear teeth, which could reduce wear and tear in certain environments where debris or contamination poses a risk to mechanical gears. Second, liquid gears could enable new modalities of motion control at micro- and nano-scales, where fabricating traditional gears is challenging or impractical. Third, the fluid medium might be leveraged to implement adaptive or programmable torque transfer by altering fluid properties in real time, such as by changing viscosity through temperature control or chemical additives.

However, the researchers are careful to note several limitations and open questions. Energy efficiency is a primary concern: viscous dissipation is inherently lossy, especially in the regimes required to effect robust coupling. The experiments demonstrate feasibility but do not yet optimize for minimal power loss or maximal torque transfer—areas that would determine practical viability for real-world machinery. Stability is another challenge; fluid flows are sensitive to perturbations, and maintaining consistent coupling in the presence of external disturbances would require sophisticated control strategies. Additionally, scaling the concept from two cylinders in a controlled laboratory setting to more complex, real-world machines would necessitate advanced fluid-structure interaction modeling and robust material interfaces.

Material choices and chemical compatibility also matter. The use of a water–glycerol mixture provides a well-characterized, highly viscous fluid suitable for laboratory experiments, but practical applications would need to consider environmental compatibility, corrosion potential, and long-term stability of the fluid in contact with mechanical surfaces. Temperature effects could alter viscosity and flow patterns, introducing another layer of dynamic behavior that engineers would need to manage.

Experimentally, achieving and maintaining the laminar flow regime is crucial for predictable outcomes. Turbulence could disrupt the orderly transfer of motion and degrade the reliability of any liquid-gear system. Therefore, the work highlights that careful control of flow regime, surface finishes, and alignment is essential to harness this mechanism effectively.

The broader scientific significance lies in reframing how engineers and physicists think about motion transfer. Rather than treating gears as rigid, interlocking components that must withstand wear and misalignment, fluidic gears invite consideration of a spectrum of coupling mechanisms, ranging from fully solid to fully fluid or hybrid configurations. This conceptual shift could inspire new designs in which conventional gears coexist with fluid-mediated couplings, offering redundancy, adaptability, or responsiveness to environmental conditions.

*圖片來源:Unsplash*

Future research directions span both fundamental and applied domains. On the fundamental side, more detailed hydrodynamic modeling and experimental validation across a wider range of viscosities, geometries, and boundary conditions would help chart the parameter space where liquid gears are most effective. Investigations into active control of fluid properties—through temperature gradients, electrokinetic effects, or responsive polymers—could enable dynamic tuning of torque transmission in operation. From an engineering perspective, researchers might explore microfabrication techniques to realize compact, integrated liquid-gear modules for microfluidic devices or soft robots, where rigid gearing can impose design constraints that fluid-driven systems can circumvent.

The potential impact on education and industry is nuanced. In teaching, liquid gears offer a compelling demonstration of fluid-structure interactions and the versatility of hydrodynamic principles in mechanical design. In industry, the path from laboratory proof-of-concept to commercial product would require substantial development in reliability, manufacturability, and cost-effectiveness. Yet the concept aligns with broader trends toward soft robotics, adaptive systems, and micro-scale actuation, where traditional metal gears may be less practical or desirable.

Overall, the Liquid Gears study contributes a noteworthy step toward diversifying the toolbox available for motion transmission. It does not claim to dethrone conventional gears but rather to illuminate a complementary approach that could be particularly advantageous in niche applications—where resilience to contamination, miniaturization, or adaptive control is valuable. If mature, fluidic gearing could coexist with traditional mechanisms, offering designers new levers to tune performance, efficiency, and reliability in ways that rigid gears cannot.

Perspectives and Impact¶

The potential implications of liquid-based gearing extend across several domains. For micro-scale devices, such as microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) and microfluidic pumps, the ability to couple motion without rigid teeth could simplify fabrication and integration. In soft robotics, where compliant, deformable materials predominate, fluid-mediated gear systems could provide smooth, programmable actuation without introducing rigid components that may hinder flexibility or safety.

From an energy perspective, the trade-off between reduced wear and increased hydraulic losses must be evaluated. In some scenarios, such as environments where lubrication maintenance is challenging or where particulate contamination would quickly wear down gears, liquid gears could offer practical advantages. In other contexts, the energy costs of maintaining viscous flows at sufficient levels to achieve reliable coupling could outweigh benefits unless high-efficiency flow-control strategies are developed.

Sustainability and materials science considerations also surface. The choice of liquid medium, compatibility with surrounding materials, and the potential for recycling and reconditioning the fluid will influence lifecycle assessments. Additionally, the interaction between fluid-driven assemblies and electronic control systems will likely become an area of interdisciplinary collaboration, marrying hydraulics with sensors, actuators, and feedback control.

Ethical and safety dimensions are not primary concerns at this stage, given the foundational nature of the work. However, as with any technology that introduces new mechanisms for motion and power transfer, considerations around reliability, failure modes, and accident risk in industrial settings would be essential as the concept matures toward real-world use.

Looking ahead, the study encourages a broader exploration of how non-solid interfaces can mediate mechanical work. Engineers may investigate hybrid systems that blend rigid gears with fluidic couplings to achieve tunable performance across operating conditions. Theoretical work could further refine models of viscous coupling in complex geometries, while experimental efforts could scale the concept to multi-body arrangements, varying shapes, and non-Newtonian fluids to broaden the range of possible behaviors.

In sum, liquid gears challenge the orthodoxy of mechanical engineering by demonstrating that controlled liquid flows can substitute for traditional gear teeth in transmitting rotation. While not a replacement for conventional gears, this approach adds a compelling alternative that could enrich the design space for future actuation systems, particularly at small scales or in specialized environments where conventional gears face limitations.

Key Takeaways¶

Main Points:

– A liquid-based approach can transfer rotational motion between two bodies via viscous fluid coupling, without solid gear teeth.

– The NYU study demonstrates this concept using two submerged cylinders in a viscous water–glycerol mixture, with motion transmitted through controlled fluid flow.

– The system’s performance depends on viscosity, geometry, surface properties, and boundary conditions, and poses trade-offs between controllability and energy efficiency.

Areas of Concern:

– Energy losses due to viscous dissipation may limit practical efficiency.

– Stability and robustness under perturbations require further investigation.

– Scaling the concept to complex machines and real-world applications remains uncertain.

Summary and Recommendations¶

The liquid gears study provides a provocative proof-of-concept that fluid dynamics can mediate motion transfer between rotating components in a controlled laboratory environment. While it does not replace traditional gears, the approach expands the engineering imagination about how to transmit power and motion, particularly at small scales or in contexts where solid gears are impractical. Future work should focus on optimizing fluid choices, geometries, and boundary conditions to maximize efficiency and stability, while exploring integration with microfluidic devices, soft robotics, and adaptive systems. Collaborative efforts across mechanical engineering, materials science, and fluid dynamics will be crucial to translate this concept from a foundational demonstration to viable technologies with broad impact.

References¶

- Original: https://www.techspot.com/news/110953-liquid-gears-challenge-5000-years-engineering-tradition.html

- Additional references (suggested):

- Fundamental fluid dynamics texts on Stokes flow and low Reynolds number hydrodynamics

- Recent reviews on microfluidic actuation and fluid-structure interaction in soft robotics

- Studies on non-traditional power transmission mechanisms at micro- and nano-scales

*圖片來源:Unsplash*